Charles Gatewood

A Chat With Charles Gatewood: Recorded and Transcribed by Joe Donohoe - Jan. 1996

Charles Gatewood is both famous and approachable. A damn nice person actually. I showed him some copies of Filth at a cocktail party (where he was drinking mineral water) and he mentioned that he would be interested in a possible interview in the upcoming issue and that he himself had put out a tabloid in New York back in the seventies and always liked to things coming up from the "underground." Gatewood has spent thirty years documenting the depths of the modern world from Bangkok to Amsterdam to New Orleans, exploring both the extremes and the median with his voyeuristic but compassionate eye, showing whoever will see, the pathology of the twentieth century and potential cures for the species' existential ills. Or maybe he's just like me and likes strippers and freaks. At any rate his work and reputation aren't a bad accomplishment for a kid who grew up in a "dysfunctional, alcoholic, hillbilly stickerpatch in the Ozarks." Getting a taste of the big world at the University of Missouri, where he first listened to jazz, met beatniks and learned about ideas, Gatewood decided that he had to be an artist and chose photography as his means of expression, feeling that it was the only medium that he could master in a short time. Charles Gatewood is probably best known for having introduced Fakir Musafar to Vale and Juno at ReSearch inspiring the legendary Modern Primitives edition of the ReSearch series.

Joe: You're often associated with modern primitives and various fetish cultures but you've been doing your work for years. I have here a copy of Sidetripping, a book you put out with William Burroughs in the mid-seventies.

Charles: I started photographing in 1964.

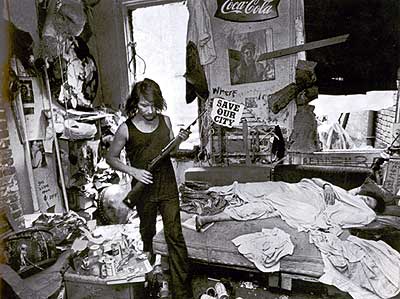

J: There has definitely been a progression and change in your work over time. I personally prefer the older images: the ones you took on the street as opposed to in the studio. They have this really raw quality to them like this one.

C: We're looking at a picture of a hippie with a gun in a crash pad in what they call SoHo now in New York. Back then they called it the Canyons, before it was developed. My early work had this savage quality and it was about madness across the board. I had a lot of axes to grind obviously. I was angry and had a lot of things to say with my work.

J: What were you angry about?

C: A lot of things uh (pauses). This was during the sixties and the early seventies and the mood of the country was very confrontational. The hard hats were beating on the hippies and the hippies were pissing on the hard hats. We were trying to stop the war and all that stuff was going on. All the revolutions that started in the sixties were still explodingŠ The Women's Movement, the Black Movement, the radical sex movement, Civil Rights, Hell's Angels, drugs. All that was really happening and the Establishment was really coming down hard on it. Everything was really polarized and there was a lot of crazy energy in the air. Sidetripping is about that really. These are sort of candid looks at the way it was. There's a little bit of everything in here. Freaks, junkies, drunks, cops, hard hats, lost people, Jesus people, gays, guys with no pants on, crash pads.

J: It's kind of interesting the way this book is laid out with just these stark photos and no captions.

C: Well William Burroughs, as you mentioned, wrote some text for this book, and the Burroughs text bounces off this in a kind of savage and poetic way. I didn't identify anything specifically because I wanted to give everything a weird, surreal, unexplained character. I don't want to spell it out. I let people come up with their own associations. I started working on this book in 1966 when I came to New York. The East Village in the sixties was just exploding. I decided to do a photography book that would show all the madness and ask the basic question "Who is really crazy here?" I've got straight mainstream types, like here's a business man and his wife drunk at Mardi Gras, just regular folks [the "regular folks" stagger inanely, the man has the plastic rings of a Budweiser six-pack looped through his belt support, the woman plows into him with an unnatural looking motion, both have the expression and appearance of rural serial murderers]. Here's a couple of hippies drunk on Bourbon Street [two hippie kids appear out of the dark. Madness can't be said to have claimed them. Two more well mannered young people you couldn't ask for]. Here's some policemen beating up a Yippie. Here's some hard hats out to kill some freak. There's an old Dylan song that goes "You write for your side, I'll write for mine." So I just wanted to put it all down and let others sort it out. I put a lot of Mardi Gras stuff in here. That's an event where people can get together and celebrate their deviance. That's where I first saw heavily tattooed and pierced guys.

J: It was a sailor thing first right?

C: Well the sailors were there first and then the gays were there right after the sailors. Like these leather guys in this photo. I took this in 1972. This guy is pierced and he has weights hanging from his tits. This is the first time I encountered all of this. Mardi Gras has some strange twists. I must have photographed it fifteen times.

J: How did you make the acquaintance of Burroughs?

C: There's this music writer in New York named Bob Palmer. He was a big Burroughs fan and played with a band called The Insect Trust. Real smart guy and great musician. He persuaded Rolling Stone to let him do an interview with Burroughs and they sent him off to London and he took me along to do the pictures. I had a dummy of Sidetripping with me and I showed it to William and asked him for an introduction. It's a long story but he ended up giving me text. Nice guy huh?

J: Did he write stuff or just take text from his books?

C: Both. He wrote an introduction and I found a publisher and they wanted more text so I went back to Bill and said I want more and he said he'd write a couple more pages and then I could just take stuff from his books. So that's what we did.

J: Photography seems like it should be the most objective of the art mediums but it's not really.

C: No. What is objective you know? It depends on what you choose to take and what you choose to leave out. Sometimes you can choose to leave out the most important part. In Sidetripping, a lot of times I used tricks to make an image a little more savage. One trick was to use the flash low. If you use the flash low with the camera at eye level you get a kind of demon light like this picture of a guy pissing in the street [three redneck looking frat guys appear in the photo. One empties his bladder while flashing a peace sign. They look like evil assholes in Charles' rendering, hell light coming up from below -- "Here's Johnny," says Jack Nicholson -- they probably were evil assholes but who knows]. I used this trick a lot around this time.

J: How did you take these pictures without getting killed? Some of your subjects seem like scary people who wouldn't like to be photographed?

C: Well I grin and shuffle a lot, as if to say: "How can I be any threat to you?" Smiling helps. I wok at a lot of public events and public events are not as dangerous as they look. I can take pictures at a parade or demonstration or protest and there's a cop over here, one over there. When I photograph bikers at Daytona Beach during Bike Week I take these pictures of these really scary bikers but it's a public event with police, it's not a biker rally out in the woods and it's a lot safer that way.

J: Do you make friends with these people?

C: Sometimes. These days I'm making more and more friends. Most of my friends these days are people I work with. In the early days though I was on the streets more, basically grabbing shots, "taking" pictures and moving on.

J: These days you are associated with the modern primitive movement. How did you meet Fakir Musafar?

C: That's probably the most important thing I've ever done in terms of changing people's thinking and behavior. I never thought this thing would be so earth shaking. None of us did. I heard about Fakir through PFIQ, the piercing magazine put out by the Gauntlet people in the late seventies. I was in New York and Fakir was out in California but I knew I just had to meet him and work with him. Annie Sprinkle ended up introducing us in 1980 and I asked him if I could photograph him and he said sure. There were these two film makers in New York, Mark and Dan Jury who were making a film about my work which ended up being called Dances Sacred and Profane. They saw my pictures of Fakir and wanted to film him doing his rituals. Now Fakir was in the garage at this timeŠ well closet really. He was working at this ad agency in the Silicon Valley, wearing these three-piece suits and driving a BMW. He was a little concerned that he might loose business if he came out with all these weird rituals that he was doing at the time -- the only people that really understood them were the radical sex people. He just decided that it was time to come out so we made the film which showed my work but then he does these rituals at the end and it kind of steals the show. ReSearch did the Modern Primitives book about the same time that we did the film. I introduced Vale and Juno to him and Vale immediately sensed that something was going on with this modern primitive idea and he was right on. Because of the book and the film Fakir came out of the closet and very quickly became a very famous guy. The idea spread like wildfire. It was in the air and the culture was ready for it. Modern Primitives is now in its fifth printing.

J: Someone like Fakir is obviously sincere but do you feel that for a lot of people piercing is merely a fashion?

C: It's hard to generalize because there's so many people doing it right now. I guess it's being done on every level from deep to superficial. I interview a lot of modern primitives for my videos and most of the people I interview have really intelligent, articulate explanations for what they're doing. I think that most of the people involved are doing it on some kind of deep level, in one way or another. Whether it's deprogramming or reprogramming, declaring their independence from the system, joining the tribe or whatever. I think most people's reasons are pretty valid. But then we have the MTV approach also. Since that girl got her navel pierced on this Aerosmith video all the piercers I know say these college girls are coming in to get their navels pierced. The New York Times even had a clip-on navel stud in their fashion spread the other day.

J: Are you involved in any of this? You seem pretty conservative by San Francisco standards anyway.

C: Well Bill Burroughs taught me that. He wears the three-piece suits himself and he's one of the most radical people on the planet. My background is anthropology and I go into the field and the world and study all kinds of unusual behavior and come back and show people what I saw. I've always found that it's good for me to look invisible or at least neutral. I've got a black leather jacket on right now but I could put on a tweed jacket and a pair of slacks and look like a college professor. Being invisible helps with my work.

J: How did you get started on this video thing?

C: Well I was living in Woodstock, New York, I had moved out of Manhattan for the most part. It's hard to be an art photographer and I wasn't doing much photojournalism and I needed to get some bucks. The 8 mm cam 'corder and the VCR came out, just about the same time ten years ago. Bingo! The light bulb went off. I can buy a video camera that makes good quality videos and I can video the same things I've been photographing and sell 'em like books, as products. It's taken ten years to really make that work but now I've got 35 videos and I can take the money I've made off them and finance myself, my books, traveling, photography.

J: You use the word "weird" a lot. Does the word "weird" have any validity anymore or has what was once marginal now become completely mainstream?

C: Let me tell you about something that happened to me two hours ago. Some film producers in LA are doing a series of programs for HBO which are a spin-off of a successful program called "Real Sex." They wanted to do a segment on body art and body manipulation concentrating on piercing and its erotic aspects. They offered me $200 to produce a segment on a heavily pierced man going down on a heavily pierced woman and talking about how the piercing accentuated their sex life. [pause] Now I wouldn't even insult a pimp by offering him $200 to do that would you? To me that's weird. We've gone full circle. The network is calling me now. When I started out this was underground stuff. It was strange, forbidden and exciting. Now it's full circle. Anytime the mainstream can take something from the underground and market it a lot of energy is released, a lot of money is made but then it's cheapened beyond recognition. It's disgusting. On the other hand we need that push/pull process. It wouldn't be any fun if we didn't have people who were trying to stop what we're doing or co-opt it. I don't want it to be easy. If it were easy than anybody could do it. I've had to bust my ass to do what I've done.

J: You need a challenge. As an artist whose career has stretched over several eras, what's your take on the fragmentation apparent in the culture today? The media and the baby boomers have given some people my age the impression that the sixties, erroneously or not, were a time of generational consensus, yet now everything seems like warring camps. Tribal as it were.

C: Well tribalism cuts both ways. On one hand tribalism is really cool. It can give you a family and a group of people that think the same way you do and a support system. You can realize that you're not alone, not powerless, all the things the system tells you that you are. On the other hand tribalism can be really conformist. If you do anything the tribe doesn't like they kick you out. You can die without a tribe. It can be stifling. How can you be a good little rebel in a tribe? There's a contradiction. The future embraces paradox, fragmentation and contradiction and it's our job to swing with that.

J: Your later photos in this book Primitives look a lot more intimate than the earlier ones. Obviously if you're photographing someone's genitalia it's more intimate.

C: Well yeah. We're looking at primitives now and most of these people are friends of mine and most of these shootings are collaborations. In the early days I took grab shots, shooting on the streets and on the run. You can see that now I'm meeting people and getting to know them. My enthusiasm is real. I know what I'm doing and they know what they're doing. You notice that there's a real trust there? Do you feel that?

J: Yes I do. It's definitely very friendly.

C: I've worked very hard to be worthy of that kind of trust.

J: Someone like this guy here, who has these deep, dark tattoos on his head, certainly had to be committed to doing what he was doing. This wasn't just some kid who ran down to the mall after smoking bad pot and decided to do this to himself to piss his parents off.

C: One thing I like about this kind of body art is that it's so authentic. You can't buy and sell this stuff. Real art goes back to a time when it was a sacred thing.

J: Shamanistic.

C: Yeah. This is Erl. I see him from time to time. This piercing across the bridge of his nose is named for him. He did it with the LA Gauntlet people. I had an opening in Santa Ana last spring and Erl came and he's got a whole new bunch of piercings and tattoos. He's got a strip from his chest cut open and you can put stuff in there now. [the interviewer laughs] He's always one step ahead. He's talking now about getting implants of marbles up and down his arms and having them wired to a pacemaker battery so his arms will light up when he moves in a certain way. He's in a class by himself.